Local to Global: New England Literature

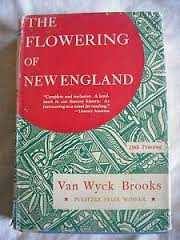

My best time for reading books is during vacation, when I can live with a book for hours at a time, maybe come back to it two or three times during the day. I can read news articles and magazine pieces on the fly, but I’ve never been someone who enjoys chipping away at a book three or eight pages at a time. I’ve given myself a casual assignment to re-read a bunch of books that were important to me early on, to remind myself of why those books made such a difference to me and helped shaped the way I feel and think. I first encountered Van Wyck Brooks’s “The Flowering of New England: 1815-1865” when I was working at the public library in Dracut, during my college years. The book traces the rise of Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne, and others, framing their work as the origin of American literature. I remember the library volume was textbook-sized with thick paper stock, probably from the first edition in 1936. Brooks won the National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize for this publication. In the mid-1970s, I was starting to think I may be able to write something that someone else would want to read. It was fortifying for me to absorb Brooks’s story about men and women from familiar places, Boston and Concord and Cambridge, creating a literature for the young nation, finding their voices apart from the European tradition, the Western classics, the great books up to their time. Now, re-reading the pages the week, I’m equally affected by the intellectual history of that time, the deep engagement with ideas, the determination of the emerging writers to have their say, and the remarkable staying power of a cluster of authors who traveled the territory we know so well. Last summer, I saw for the first time at the Concord Museum the desk at which Thoreau sat to write much of “Walden.” There it was, Thoreau’s desk, a few feet away. Van Wyck Brooks’s account references Lowell’s textile mills and farmsteads in Pepperell and elsewhere in our area. I’ve heard that Emerson lectured in Lowell more than 20 times when he was on the lyceum circuit. And we know that the Thoreau brothers skirted the mill district of Lowell when they traveled the Concord and Merrimack rivers on their weeklong journey north into New Hampshire. “The Flowering of New England” is a local story whose substance is of global interest. Everything has to start somewhere.

“[Frank B.] Sanborn was even a member of the Walden Pond Association. So the ‘Sunday walkers’ were called in the village,—Emerson, Alcott, Thoreau, and one or two others who never sat in pews. One had to pass a stringent test to belong to this society, severer than the Athansian creed. There were only two or three persons with whom Thoreau, for one, felt that he could afford to walk, his hours were so precious. Was Emerson less exacting? He was only more polite. In the presence of cranks and bores, he masked his irritation. Henry trampled on them. … With his long swinging gait, his eyes on the ground, his hands clasped behind him, his legs like steel springs and his arms as powerful as a moose’s antler, thrusting brush aside, with his wary glance, his earnest energy, as if, on the lookout for squirrels, rabbits, and foxes, he was in the thick of a day’s battle, Henry was no man to trifle with. … No matter, he was a virtuous walker. He had eyes for every line and every colour, for every fleet of yellow butterflies, ears for every sound, the wood-thrush pitching his notes in the pine-alleys, the oven-bird beating his brass in the heated shades of noon, the patridge’s feathery roll-call, the gossiping dialogue of the brown thrashers, a comforting sound, this latter, enough to cure the heartache of the world, on one of those summer days when the sky bends over a walker with a face like Jerusalem delivered. …”

—Van Wyck Brooks